Maryam Elizondo thinks she might be “a little too stubborn.” Given that she will soon enter the MD, PhD program at a major medical center in Houston—after earning her bachelor’s degree from the Rice Department of Bioengineering—it seems a dose of stubborn has served her well.

Born in a Rio Grande Valley border town, Ms. Elizondo learned English in second grade. However, her native Spanish allowed her to pour through her father’s textbooks from medical school in Mexico.

If her dad’s textbooks sparked her interest in medicine, her next bit of inspiration came from her high school physics teacher. After the thrill of being accepted to Rice University Elizondo was confronted with picking a major. But she wasn’t sure what a major was—her dad had gone from high school to med school. Pointing out that Maryam excelled in biology and physics—and loved robotics club—her teacher suggested bioengineering.

Maryam agreed it was the perfect fit. But, then she arrived at the Rice campus. “The students I met said everyone they knew in the bioengineering program had dropped out because it was so hard. In fact, the freshman ‘me’ wouldn’t believe that four years later I now have my bachelor’s degree in bioengineering—maybe I was just being stubborn.”

She attributes much of her early success to the Rice Emerging Scholars Program (RESP.) RESP assists freshman from high schools that provide limited college preparation. The students spend the summer getting ready for the academic rigors of a top university.

In addition to learning college-level organization and study skills the RESP experience was an eye-opener for Elizondo. “They are all very bright students who were accepted to Rice. What was surprising—or maybe not so surprising—was that bright students that happen to come from high schools with limited college prep also happen to be underrepresented minorities.”

However, a strong upside to the make-up of the RESP group is the confidence that the participants gain throughout the summer. “When you are in a group that looks like you it is easier to express your opinions. Your confidence grows when you notice that people are listening to you and really taking your ideas seriously.”

Another inspiration was bioengineering professor Dr. Anne Saterbak—a faculty leader in the RESP program who, like Maryam, came from a small town where young women rarely went to college. Saterbak inspired Maryam with a deceivingly simple “mantra,” “I can do hard things.” In her senior year, to “give back,” Elizondo became a RESP fellow—undergraduates that assist the faculty with each new crop of students.

As a RESP fellow she gave talks on bioengineering as she was gaining a lot of expertise from her classes and as a Research Scientist in the laboratory of Dr. Antonios Mikos. Given that within a year she had co-authored two research publications, it seems she has convinced herself that not only can she do hard things, she prefers them.

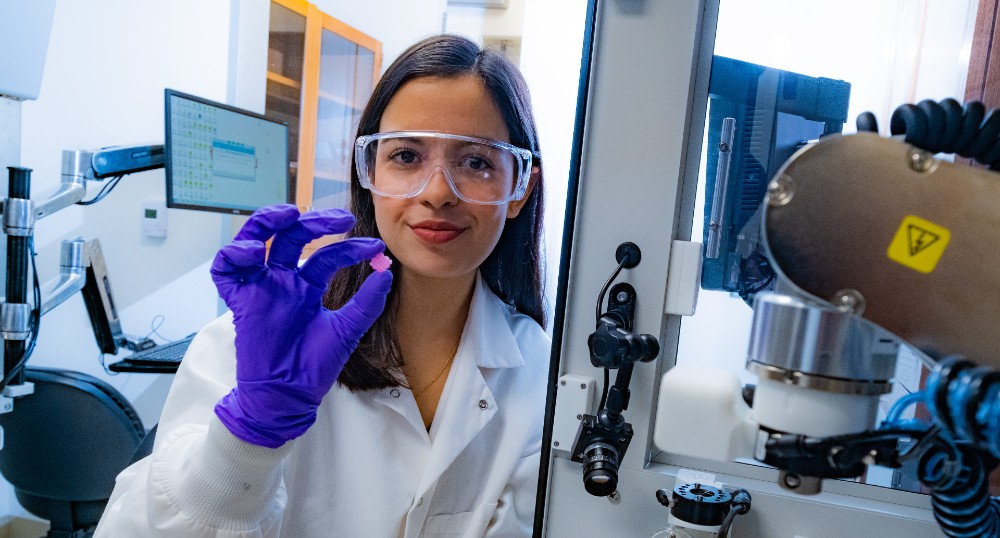

Ask Elizondo about the lab and you will get a comprehensive description of her work using 3D-printing to create biodegradable polymer scaffolds for regeneration and repair of tissues—most notably bone and cartilage.

“Repairing bone and cartilage injuries is challenging for a number of reasons,” says Elizondo. “The vast majority of tissues in the body are soft. Only bone and—to a certain degree, cartilage—are load-bearing hard tissues. Because they are load-bearing, repairs have to be incredibly sturdy and mimic the natural tissue as closely as possible. We need to be able to implant a repairing scaffold that can regenerate bone and cartilage and in a configuration that matches the injured area.”

Elizondo and her colleagues created a process that allowed them to 3D-print a polymer scaffold while also loading live cells that are precursors to bone and cartilage—without damaging the precious tissue-regenerating cells. One of the novel aspects of the work was the ability to load the different cell types into the successive “tiers” of the scaffold so that the implant could promote bone and cartilage regeneration in successive layers—just like it is laid down in normal circumstances, for example, in the knee.

Elizondo’s research experience altered her, and her family’s “Plan A” for her future: to earn her M.D. and practice medicine. Becoming a Ph.D. researcher in bioengineering—call it Plan B—was becoming increasingly exciting to Elizondo. “I really like working with my hands in the laboratory and the challenge of developing a bioengineering solution to a medical problem,” she said.

Elizondo says she couldn’t understand how she could help patients as a medical doctor without working in the lab to develop the novel technologies needed to solve their problems. The answer? Plan C, summed up by Elizondo with: “what the heck, I’ll do both.”

Right now, doing both might come in the form of becoming an M.D, Ph.D. orthopedic surgeon. Although she hesitates, “Orthopedic surgeons are generally big burly guys that get in there, break bones, get out the tools, screw ‘em back together…” One can picture her mimicking a carpenter pulling tools from his belt, measuring, realigning, tightening. She mentions that she is five foot four and 115 pounds.

Her current thought on the matter isn’t exactly a shocker. “I think I could still play with the big boys if I put my mind to it.” As an afterthought she suggests that she wouldn’t enter the male-dominated field out of stubbornness, it’s more that she is “really determined to meet my goals.”

So, she is off to start the Medical Scientist Training Program (MSTP) in Houston in June. Does she have any advice for young women interested in biology? “Be resilient. It will help you develop grit that can keep you hanging on in difficult situations. If you’ve never coped with a tough situation, what will you do when one arises?

“Really, difficulties are a blessing in disguise because when the next one comes up you can remind yourself ‘I can succeed in difficult situations.’”

So it seems clear that Elizondo has not forgotten her first mantra “I can do hard things,” given to her by one of her first mentors. She has just continued to fine-tune it as she moves through the progression from being a mentee to becoming a mentor.